Audacity

Audacity is a time-honoured and widely used free software audio editor, used by a staggering number of audio hobbyists and professionals alike. Whether you are primarily an audio artist or not, you probably should have Audacity installed on your computer; it's just that useful.

Strengths [Weaknesses]

Intuitive

If you can use a text editor, you can edit sound with Audacity.

No Setup

No need to use Audacity with JACK, or configure plugin, or deal with routing. Audacity is basically self-contained.

Powerful

For its simplicity, Audacity can be made to produce amazing results.

Weaknesses [Strengths]

Not a DAW

Audacity is not a sequencer, it does not have plugin soft synths, and it has no concept of auxiliary sends and returns for effects.

Not Non-Destructive

Digital audio workstations render sound in regions or containers, so the user only edits an instance of the sound. Regions can be cut and restored at any time, effects are applied to tracks rather than the sound itself, and so on.

This is called non-destructive editing, and Audacity does not have it. This does not mean that your sound files are destroyed when edited in Audacity, but it does mean that Audacity's workflow is less flexible than a full-featured DAW.

Install

There is a Slackbuild for Audacity on http://slackbuilds.org, but for maximum flexibility, it should be installed only after soundtouch, twolame, and ffmpeg have been installed. If you used the Slackermedia-huge queue file, the first two are, but to verify:

$ ls /var/log/packages/ | \ grep -E -r 'soundtouch|twolame'

If you need to install either library, do so through http://slackbuilds.org (you can use sport from a shell, or visit the SlackBuilds website directly).

Read the section on installing ffmpeg to learn more about that.

Assuming everything is properly installed, install Audacity. The build will auto-detect the libraries needed.

Stability

The version of Audacity, as with any application, is extremely important. Releases can be frequent with Audacity, but not all releases are equal. Find a good release and stay with it for as long as it continues to meet your needs. There are official “stable” releases, so consider using one of these.

In other words, steer clear of using the latest release just because it's the latest release. Use the application for its features and stability, not because it has a higher version number.

Sometimes the SlackBuild available might exceed your differ from your desired version. If this happens, you can still use the SlackBuild; you just need to change the version number that the SlackBuild script looks for when it attempts to build the application.

If you find the need to change the version that you are compiling with Slackbuilds:

- Modify the

VERSIONline in the SlackBuild script to the desired version. - Manually download that version of the source code into the

SlackBuilddirectory. If you don't know how to locate the source code, look at the.infofile for a hint. - Execute the SlackBuild script to build it, and then install with either

installpkgorupgradepkgas appropriate.

For instance, to change the version number from 2.0.5 down to 2.0.3, you may

use sed:

# sed -i 's/VERSION:-2.0.5/2.0.3/' audacity.SlackBuild

Alternately, just open the script in a text editor, if that is more familiar to you.

Slackermedia Audacity Keyboard Shortcuts

It is common for “pro” applications to use this paradigm: one hand on the mouse for cursor control, one hand on the keyboard for quick tool or function changes. This model works best when tools and functions are mapped to single key strokes (as opposed to requiring the control or alt key plus another key). By default, Audacity uses few or no single-key shortcuts, but, it being open source, this can be changed easily if you consider yourself a “pro” (or impatient) user.

If you love Audacity's shortcut layout, then don't feel like changing it is going to give you special powers; this is simply a different shortcut scheme that you may use if you find it useful.

Download the official Slackermedia Audacity power-user config file and place the audacity.cfg file in your ~/.audacity-data directory for a better UI layout and keyboard shortcut scheme.

The UI layout of Audacity on a Slackermedia system is minimal, removing excess toolbars such that only audio input and ouput settings, sample rate, VU Meter, and the tools remain.

The keyboard shortcuts are simplified and are aimed for more efficient work.

| Function | Key Sequence |

|---|---|

| Tools | |

| Selection (I-Beam) | i |

| Envelope | e |

| Draw (Pen) | p |

| Time Shift | t |

| Record | r |

| Selection Commands | |

| Lift Delete | d |

| Ripple Delete | x |

| Silence Audio | s |

| Split | k |

| Join | j |

| Trim | h |

| Find Zero Crossings | z |

| Navigation Commands | |

| Play 1 Second | 1 |

| Play to Selection | b |

| Play Cut Preview | c |

| Transport Left | ] |

| Transport Right | [ |

| Transport to Start | Home |

| Transport to End | End |

Using Audacity

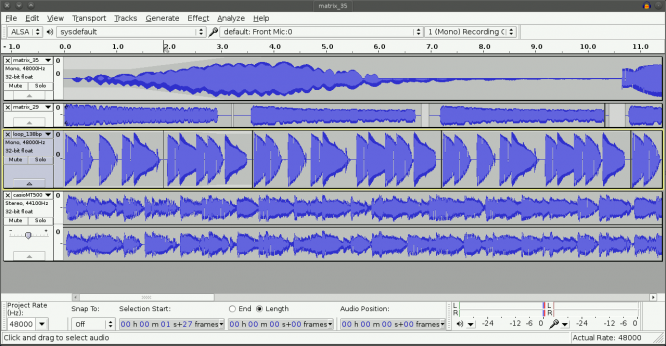

The basics of Audacity are surprisingly intuitive. If you have used a word processor, then you already know most of the basic functions of Audacity. Even the workflow is similar; import or input content, style and arrange it, export for delivery.

If you have no little or no experience with editing audio, this may be a great all-round tool for you, but if you are used to full-featured digital audio workstations then you should regard Audacity as a feature-rich multi-track recorder. It is not a DAW, and even though it is extremely powerful and flexible, that doesn't mean that its underlying technology is anything but a fancy multi-track recorder.

If you are not an experienced DAW user, this will mean nothing to you, but for those who are used to a DAW: tracks in Audacity are not like tracks on a mixing desk, because there are no busses in Audacity but the master bus. A track here is more like an immovable audio clip in a DAW. You can move audio into and out of the tracks, but you cannot move the tracks in time nor can you alter a track's length because every track is always as long as the project itself. You do not apply effects to tracks in Audacity, you apply effects to the actual audio file itself.

The structure of Audacity begins with an empty work area. Within this space, you can create audio tracks and into these tracks you can import audio files.

Importing Sound

If you have sound files that have already been recorded, import them from the File menu > Import > Audio. There are few formats that Audacity cannot use, as long as you have done a full install.

In the event that a certain filetype cannot be imported, you probably have an

application that can convert it into a suitable format. The Slackermedia build

of ffmpeg includes nearly every codec that can be included, so it is the best

bet:

$ ffmpeg -i input.foo -vn output.flac

- ffmpeg invokes the

ffmpegcommand - -i input.foo sets input file to

input.foo - -vn disables video (think “video=null”)

- output.flac saves the converted file to the current directory as file

And then import the converted file and get to work.

Recording Sound

Audacity can also be used as a recording platform. To record into Audacity, set the input source in the Device toolbar, or set the default device in Edit > Preferences > Devices.

Given the extreme diversity of computers that Linux manages to support, the audio menus on Linux may sometimes (depending on your hardware) provide more options than seemingly necessary (until, that is, you need them). Do not be alarmed by a long list of audio inputs when you yourself can only think of one or two on your computer; instead, learn how to manage your audio in the Linux Audio section.

Once you have selected the correct audio input device, start recording: if you are using the Slackermedia config, press r. Otherwise, click the Record on the Transport toolbar.

Editing Sound

Selecting, moving, and targeting audio clips is done with the Select Tool (the I-beam). It is essentially the same process as with word processing; select the target area that you want to affect, and then perform some action on the area. The obvious difference is that you can read text in a word processor but you need to listen in Audacity. Play audio with the Spacebar or the Play button on

the Transport toolbar.

Deleting and Cutting Sound

If you hear sound that you want to remove:

- Switch to the Select Tool (the

ikey if you are using Slackermedia shortcuts). - Select the part of the sound that you no longer want. It's normal for you to have to play a section of the file over and over again until you find just the right place to begin and finish your selection. For this reason, in fact, once you make a selection, the default action for

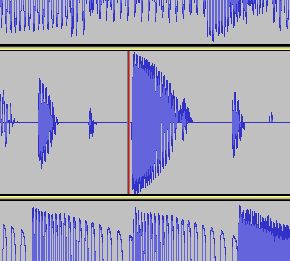

Spacebaris to play just the contents of the selection. This way, you can adjust the selection until it's encompassing exactly what you want. - Usually you will also want to find Zero Crossings, that is, snap your selection to the closest crest or trough of the selected waveform, meaning that after you make your splice, the waveforms on either side of your selection will be able to meet at a common point rather than having to distort and warp to form a complete waveform again.

- To conform your selection to zero-crossings, click on the Edit menu and select Find Zero Crossings (or press

zif you are using the Slackermedia config).

There are two types of removing audio in Audacity:

Split

A split delete or split cut removes the selected audio, leaving all audio occuring afterwards uneffected. In video editing, this would be called a Lift. To perform a split delete, press Ctrl-Alt-k (or k if you are using the Slackermedia config). For a lift cut, use Ctrl-Alt-x.

Delete or cut

Removes the selected audio, and moves all audio after it backward (screen Left) in time. In video editing, this would be called a Ripple delete. Press Del (also x, on the Slackermedia config) for deletes. For cuts, use Ctrl-x.

A standard cut (but not a standard delete) leaves behind a visual scar, of sorts, marking where you have just cut out audio. This is actually a convenience Undo feature; click the marker, and the cut audio will be returned in place (but you will also still have a copy in your clip-board). In other words, it converts a cut to a copy.

Right-click the marker to heal the audio region; the audio remains cut. but the marker disappears. There is no harm in leaving the marker, except that sometimes it might get in the way and restore audio that you did not mean to restore, or just be visually distracting.

Copy Paste

Copying and Pasting audio back in is as straight-forward as you would suspect: select audio, find the zero crossing as needed, copy or cut; find a new location for the audio, place the Transport there, and paste.

Every paste is an insert paste; in other words, if you paste audio onto a track already containing audio on it, then any audio to the right of your paste will be pushed forward (screen Right) on the timeline. There are no overwrite edits in Audacity.

Adding and Removing Silence

If for any reason, you want to silence a region of audio without deleting or cutting, you can overwrite a region with silence. This avoids a break in the sound file that you have loaded.

Generate silence by selecting an area of your sound file and clicking the Generate menu and selecting Silence. By default, the start and end point of silence matches your current selection, so press Return to continue.

Conversely, remove silence from a region with the Truncate Silence effect: select a region of audio and click on the Effect menu and select Truncate Silence. In the Truncate Silence window that appears, provide the minimum contiguous duration of silence you want removed, the maximum duration, the ratio of sound-to-noise that you want considered to be valid silence, and the decibel level under which any silence must fall in order to qualify for removal. Click the OK button to execute.

Moving

Move clips of imported audio forward or backward in time with the Timeshift tool in the toolbar (Slackermedia: t). Audio clips can be moved within a track or to another track entirely. There is not necessarily any harm in leaving empty space between clips of audio, but be aware that effects in Audacity do not carry over into empty space, so if you apply a reverb effect to an audio clip of someone saying “Hello World”, but leave a space between the “hello” and the “world”, then the reverb itself will abruptly end at the gap, and resume (assuming you had it selected when applying the effect) for the “world”. The fix for this is easy; just fill the gap with silence, but if you find yourself hindered by this design, then consider using a DAW.

You can also align the contents of tracks relative to one another, to your cursor, or to selection bounds, from the Tracks > Align Tracks. Try it by importing a few tracks, selecting them, and then running Tracks > Align Tracks > Align Tracks Together.

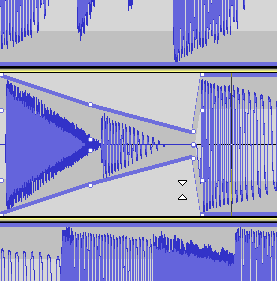

Mixing

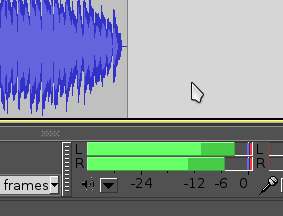

Audacity has mixing capabilities in two senses: you can adjust the volume and stereo position of sounds, and you can automate the mix so that volume and position change over the course of a project.

However, Audacity alone has no inbuilt Master Out track, so an experienced audio engineer seeking the main out track upon which to place a limiter or compressor will be disappointed. You have to monitor the levels manually, but since everything is baked in to the tracks, one run through the project is a reliable reading on what levels the project reaches.

Sound monitoring, to the inexperienced, might feel a little upside-down; the loudest safe level for speakers to output is marked as 0dB. Levels less than 0dB are logarithmically quieter. Related to that are these two things to keep in mind about sound: loudness is relative, and sound is cumulative.

Loudness is relative in part because you can never be sure whether your audience has their speakers turned up very loudly or turned down. So it does not suffice to blindly insist that a sound effect of an airplane is definitely louder than chirping crickets, or that a cymbal crash is louder than a bass flute, because you can mix them such that they exist at the same level of loudness, or you can mix them such that they are nearly at the same level. If you want some sound to be definitively louder than others, then you must mix it that way.

The way to mix one sound louder than others is to make sure that softer sounds are hitting lower dB marks than loud ones. Seems obvious, but it can be surprisingly easy to get hold of, for instance, some chirping birds that is naturally loud, because the sound recordist's goal is to get clear and audible samples of birds. You as the mixer, then, must mix them down to some level that is, relative to your main dialogue, soft and distant.

The traditional level for a “normal” speaking voice is -15dB (for movies, or media with a high bandwidth for dynamic range) or -12dB (for television, or media with lower bandwidth for dynamic range). All other sounds should be “loud” or “quiet” in relation to this establishing level.

The upper limit for the final output of Audacity should be 0dB, or to be slightly conservative, -3dB or thereabouts. Anything in excess of 0dB will probably distort on the final output at best, or cause damage to a user's speakers at worst.

Keep in mind that when sounds are played together, their cumulative output is louder than either of the two played separately. Expect a drum mixed to peak at 0db and backing guitar mixed at -6db to push the volume meter over the 0dB mark. You don't necessarily need to calculate these things in your head; mix sensibly, knowing the ebbs and flows of your soundtrack, and then listen to the project and fix the spots where the sound is too loud or too quiet.

There are three tools that help you mix in Audacity:

- Set initial values for volume and stereo panning in the track sidebar with the volume and panning sliders. Monitor Audacity's output levels in the Monitor Toolbar. Red is bad. A more traditional view of these controls is available from the View menu > Mixer Board.

- Make on-the-fly changes to volume with the Envelope tool, available from the Tools Toolbar (Slackermedia config:

e). With the Envelope tool, click on the border of the imported audio region and drag; with the click, a node or keyframe has been created, and by pulling it lower into the track, you reduce the volume. Click and drag to create more nodes. Use this technique to create selective volume control. This is a very effective method of automating the mixing process, and can even be used, at times, in lieu of more traditional tools of the trade, like a like limiters. - Use the Effect > Amplify effect to lower volumes of tracks. It's usually better to adjust the track's volume slider but there may be times when a sound is just too quiet or too loud and it just makes sense for you to change the sound level.

After mixing, listen to the final project carefully, and keep your eye on the volume level, as shown in the Meter Toolbar.

Track Management

The Tracks menu provides most (but not all) functions for managing tracks.

- Tracks > Add New > Audio Track defaults to a mono track, so use Stereo Track if you need a stereo container for stereo-coupled audio. Mono audio cannot be moved to a stereo track, and stereo cannot be moved into a mono track.

- To mix a track down to a single mono audio stream, click on the track to make

it active, and choose Tracks > Stereo Track to Mono.

- To convert a stereo track into two separate tracks, click the track name (the label at the upper left corner of the track) and select Split Stereo Track or Split Stereo Track to Mono. The former keeps one track as Left and the other as Right, while the latter marks both of the resulting tracks as Mono.

Effects in Audacity

The model for mixing that has been established for sound engineering is one of busses, and it has been ever since hardware mixing desks. The idea is that a sound source (a musical instrument or a voice, for example) is captured with a microphone, which sends the sound into a mixing desk, which might then send the sound over to, for example, a reverb unit (essentially a sub-mixer) and then the sound, plus whatever amount of reverb is added, back to the track, and to the monitor (speakers). It's a pipeline, with flexible structure and optional outboard diversions.

Since Audacity does not seek to emulate that pipeline, this is not how Audacity processes audio signals.

Audacity calculates effects based on the audio stream contained in a track and then applies the results back to the audio stream. The only way to change the effect then is to Undo, recalculate and re-apply. This means that an audio stream must be present in order for an effect to be heard, so if you apply reverb or an echo delay with a 2 second decay to a piece of audio one second in duration, you will only hear one second (probably less, depending upon the response time and tail level) of reverb. To hear all two seconds, generate a second or two of silence and attach it to the audio clip, then apply the reverb.

Audacity ships with several common effects, but since it is compatible with LADSPA, it has full access to any LADSPA effect you have installed, including the Steve Harris LADSPA pack installed by slackermedia-huge.sqf.

Saving

Saving your work in Audacity can be done in two ways; you can export to an audio file or you can create a project file to save all of your changes in a format that Audacity can continue to edit later on. With few exceptions, it is recommended to save your project, and export your work for your final product.

Creating an Audacity project is as simple as choosing File > Save Project. An Audacity project is not self-contained by default, so it behooves you to create a new folder to hold your project files, or else use Slackermedia's Planter application to manage your projects. If you use a Planter directory structure, place the Audacity project file (the .aup file) within the sound/session directory.

A project folder is created by Audacity and placed alongside of your .aup file; it contains edits of audio clips used in your project and is meant to be used by Audacity rather than by humans, so it's best left alone. To that end, Audacity will by default prompt you whenever you import audio to either make a copy of the audio into its project folder or to just use the file as-is (change the default in Audacity Preferences). This boils down to linking or embedding (or dynamic versus static linking, to use a software analogy); if you feel that you are managing your audio files carefully (Planter helps with this) then there is no need to copy files to Audacity's directory, but if you have no structure for keeping dependent audio sources along with the Audacity edit, then you should allow it to manage audio for you, at the cost of larger Audacity project folders.

Exporting

At some point, you will want to export your project as a self-contained, distributable audio file. Since there is no Master Out channel in Audacity, listen to your entire project carefully before exporting, monitoring the output levels for distortion. You may not hear distortion in Audacity but if the volume meter exceeds 0dB then there will likely be distortion in the final output. Either go back to the problem areas and manually adjust the volume.

When ready to export, set the sample rate for your exported file in the Selection toolbar.

To export, select File > Export.

In the Export window, set the audio codec that you want to use with the dropdown menu in the lower right corner. This menu is populated according to the codecs that you have available on your system, so on a full Slackermedia install, you should have access to every major audio codec, even if only by using an external export engine.

Inbuilt Codecs

For all of the inbuilt codecs:

- Type in a name for your exported file in the Name field at the top of the window.

- Choose where you would want to place the exported file in your filesystem.

- Optionally, set options for the codec (such as quality or bitrate) using the Options….

- Click the Save button in the lower right corner.

- For some codecs, you may be prompted to fill in optional ID3 tags.

Exporting Using External Programmes

To use an external programme for exporting:

- Select External Program from the codec dropdown menu.

- Click the Options button at the bottom of the window.

- Enter the command you want to run in the Command field.

- Place a tick mark next to Show output to be notified when the external command has finished running.

The syntax of the command will depend upon what external application you are invoking; for example, to pipe audio through speexenc:

speexenc --quality 5 --comp 5 --vbr --denoise --author "Slackermedia" - "%"

But to send it through lame:

lame - "%f"

In both cases, the - represents a path to standard in and %f is a place-holder for the output filename placed in the Name field. In other words, the application (lame or speexenc or whatever) opens a tunnel to standard in as its source of input data, and Audacity sends its output data to standard in, and thus a connection is made. Not all applications accept data from standard in, but many encoders do, so generally this should work. The place-holder of %f in this context makes your external command non-specific to the project, so that you can use it later on.

What command you use and how you use it is dictated by the command syntax itself; if you are not a regular user of the encoder that you want to invoke, look up the syntax and do a few tests in a Unix shell first. Running it as an external command from within Audacity is not the way to learn an encoder, so get familiar with it first, and then try invoking it from within Audacity.

More Information

The full official Audacity manual is online at http://manual.audacityteam.org/o/index.html

See Also

Sox